Belarus

What to do When the Masters are Fighting?

Originally published in The Laboratory of The Future as «Белоруссия: Что делать, когда паны дерутся?».

Ed: The Laboratory of The Future updated this article with the following information: “While this article was being prepared for release, Zabastbel has begun taking the first steps in the right direction by separating the workers’ struggle for their rights from their masters’ power squabbles.”

Due to the information provided by our comrades at Poligraf Red and others, we can finally talk about the situation in Belarus. Teaching comrades abroad is not the best thing to engage in, but some issues are better observed from afar. Either way, we’re judging from our position in Russia. And the thing we’d like to underline: many don’t see the third party in this conflict—a simple working-class Belarusian.

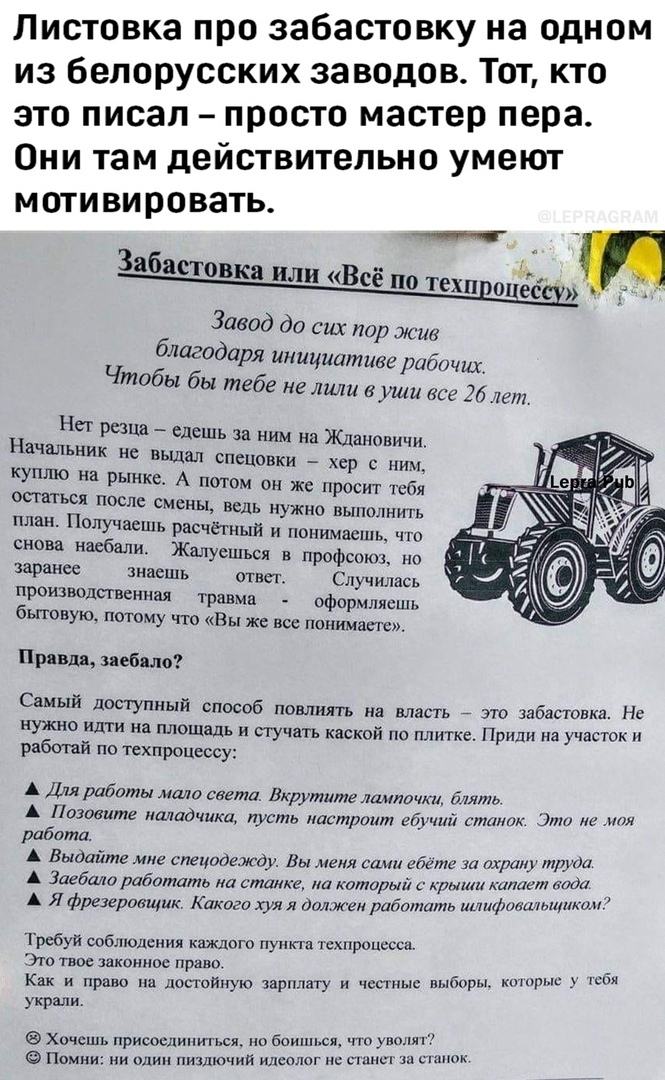

And yet, theirs is the name that gets co-opted by both the power and the opposition. It’s their support that both Lukashenko and Tikhanovskaya count on. No wonder: without the workers, factories will be in a standstill. Like one of the workers’ flyers aptly says: “no fucking ideologue will ever be caught behind the lathe.” Moreover, without the participation of the masses, both sides of the squabble will not be able to actualize their intentions. So let’s take a look at the reasons behind the masters’ fight before we get in with our serf scalp locks.

Ed: The text above the leaflet reads: “Leaflet explaining the strike at one Belarusian factory. The one who wrote this up — a true wordsmith. They really know how to motivate you there.”

So why the fight?

First, the contention is not whether further privatization and an offensive against hired workers’ rights will happen. If Lukashenko wins, he’ll continue them, too, willingly or unwillingly, just because he won’t get any new loans in Russia, China, or, most importantly, Europe. So Bat’ka, Daddy-O, as he is nicknamed in Belarus, is in no rush to criticize the economic part of his opponents’ program. It’s even easier with Tikhanovskaya and company—liberal economic reforms are written down in her program. However, its full text is kept under the radar, out of sight of the protesting masses. Like, we’ve got to handle the dictatorship and fight police brutality first, we’ll see about it later. This way, both sides try to stay increasingly mum about the most critical issue—privatizations.

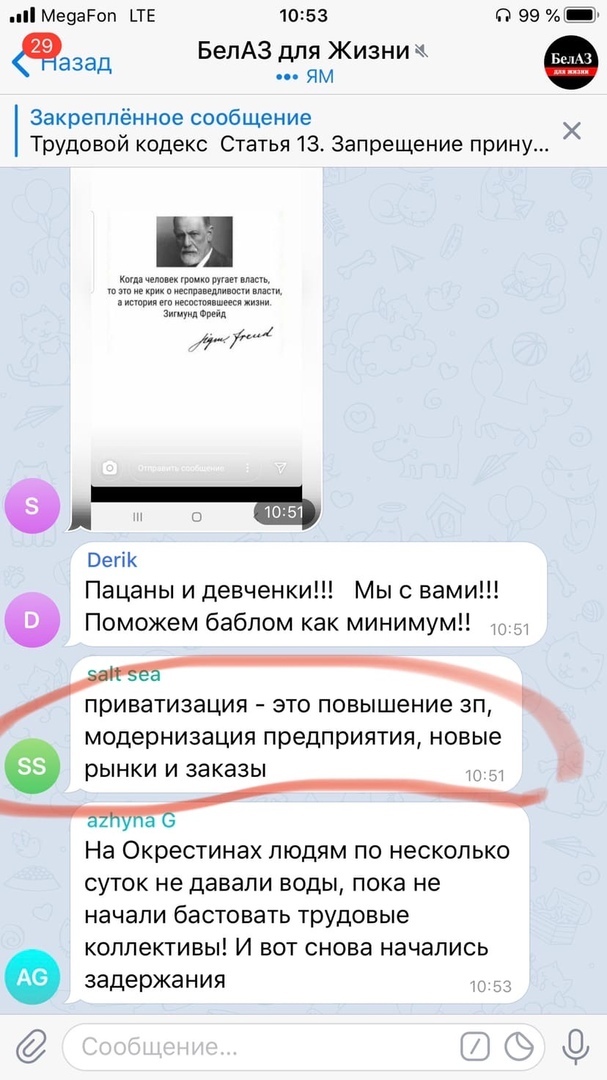

Second—the question of whether Belarus will become a democratic republic or a dictatorship is not at the center. It’s no surprise that the people have a saying: our democrats consider democracy to be the power of the very “democrats.” If this is not obvious to you, please admire contemporary Ukraine or recall Yeltsin’s Russia. Or gawk at how people talking against privatizations get banned in online communities centered around “strikes.” There you have it: freedom, glasnost, the plurality of opinions.

Ed: The circled message reads: “Privatization — means a pay-raise, the renovation of facilities, new markets and investors.”

But there’s a more profound reason. Today, a regular working person has no stake in either a democratic republic or a dictatorship. What the real “bloody bolsheviks” talked about a hundred years ago, what was always harped on

about in Soviet party schools, turned out to be true. Every single world power, even the most democratic one, implies a dictatorship. The question is: who is in control?

about in Soviet party schools, turned out to be true. Every single world power, even the most democratic one, implies a dictatorship. The question is: who is in control?

Thirds,—neither of the parties is backing a strong, really independent Belarus. The fact that Belarusian so-called “zmagar” warriors are fed by European grant money is not a secret to anyone. Their sovereignty lives in Warsaw, just like the sovereignty of Ukrainian nationalists can hail from anywhere—Munich, Toronto, Washington, just not Kyiv. But Lukashenko has also been looking for his primary support in foreign patronage lately. No surprise there: it’s hard to count on the thoroughly robbed and numerously swindled people. So he has to prostrate himself before Russia, before China, whoever is in the way. An affectionate calf will suck two mothers’ tits.

But why are the masters fighting then? What keeps them from joining in an embrace, despite the common interests? The power and the opposition can’t decide who will continue the privatizations and other anti-people reforms—and who will get to skim the cream from robbing the people. As they invite the people to join the fight for this prize, each on their own side, they put the regular Belarusians in the position of Gogol’s officer’s widow, who flogged herself. We don’t think that you like this role.

Both are worse

So, whoever wins in this fight between a rock and a hard place; they will still engage in reforms that will negatively affect the Belarusian worker. Meanwhile, our brothers will not be allowed within a hundred meters to holding power. But that doesn’t mean that we should just resign from the struggle and let things work out on their own. However, it’s clear that one won’t score a minimal advantage by taking one of the sides. While Lukashenko’s party is offering the Belarusian worker to shut up and persevere, liberals blur over the worker’s lawful discontent with the fascist symbolism with their sheer presence and, what’s even worse, lead to a betrayal of one’s interests. “To not be a bastard,” as the Belarusian protest song goes, in fact, means not picking from these two equally shameful options.

Some say that Lukashenko will finish off social services and sell factories a bit slower. But what exactly is the difference whether you’re being robbed quickly or slowly? And who can guarantee that Lukashenko will act as he did twenty years ago, and not bend over for a new foreign investor amidst the commotion?

Other smart alecks pontificate the opposite: democracy makes liberal reforms more tolerable. Let’s pretend for a second that you still think that there is a difference between liberal democracy and a dictatorship. But history teaches us the complete opposite. In Chile, where Pinochet’s dictatorship caused the liberal pogrom, the local workers and students even managed to take some things back. For instance, free education. In Russia, the majority of reforms were carried out way more peacefully. And that’s why we’re on the course to have it way worse than in Chile very soon. There’s also a lovely country called South Korea, a respectable democratic state, where strikes are repressed in a way that Lukashenko’s most evil cops can’t even imagine. And to no effect: the world society keeps mum.

Just because Chilean workers and students know how to independently fight for their rights, without expecting handouts or directions from above. Here, my friends, lies the answer to all questions: self-sufficiency.

Self-sufficiency above all

Politics has just two tools—big money and large masses of organized people. The former is not something a hired worker can possess. So, to defend their interests, one has to come about the latter. Moreover, whatever the equation is, there are always twice as many serfs as there are masters and their toadies. But an organization only makes sense when it’s self-sufficient and does not dance to someone’s tune.

Yes, bourgeois politicos have the experience, the skills, and the resources. So it’s very tempting to find a well-doer who will promise you to do everything in the finest fashion. And then will just use you for their own advantage. There are special joints for that, which are sometimes called unions. A poor worker, who had been swindled by the employers, comes to those nice men, and they, for free or a symbolic amount of money, protect the worker’s interests in court. These structures are aptly called client-oriented. Not after the clients who are always right, but the clients of Ancient Rome, the plebian flunkies to the wealthy and noble patrons.

We think that life has taught you without our help that not everything that’s called a union is aimed at the protection of workers’ rights. From an official union, the scion of the Soviet All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions, you get squat. And a box of chocolates for the kids to celebrate New Year’s eve. Don’t expect any heroic deeds from the near-liberal joints like Belarusian Independent Union. After all, Polish “Solidarity” was also a union led by the electrician Lech Wałęsa. However, it was merely an instrument for the powers alien to any working person.

Moreover, not every strike is a form of defense of workers’ rights. Liberal cannibals threw Allende off in Chile with a little help from striking truck drivers. Corrupt union leaders helped suffocate the Chilean people with hunger. Some skeptics think that something like that is already happening—and, indeed, European business structures are offering the striking Belarusians handouts. If you really want this money—take it, but don’t be in a rush to work for it. Here you can finally take the example of the bourgeois, who spend their lives conning everyone—partners, the government, and, first and foremost, the worker. After all, the dealmakers and the politicos abroad aren’t any better or more honest than the ones at home. If they give you a kopeck—it’s so that they could take away a whole rouble at a later stage.

And we don’t mention conning just for effect. Take a look: first, Tikhanovskaya promised to leave politics right after the hypothetical “honest elections” occur. The next thing we know, she’s already proclaiming herself a national leader and divvying up the minister seats. In polite company, people get beaten with the candelabra for such tricks.

There is one way out—to create unions, strike committees, initiative groups, and others yourself, from the ground up. And within existing organizations, it’s crucial to elect people you know, respect, and see leading the same life you lead. Yes, the absence of experience, connections, money, and media resources will be a disadvantage. Serious results will not come anytime soon. But on its own, independence from both factions of fighting masters is precious. Real success will come once the self-sufficient organization grows stronger and becomes tempered in battle.

Not just the factories

Obviously, we’re not talking about workers in the narrow sense of the word,—people who stand at the lathes, work on construction sites, etc. The capitalist doesn’t really care what he pays the minimal mage for: the labor of a miner or teacher, electrician or custodian, server, or even soldier. The most important thing is that for them, we’re disposable—gnomes, who will dig some more, as Russian oligarch Prokhorov had said. It’s often not important for us where and how to earn money—physically or intellectually, by using contractors or in government structures.

Why are we reminding the reader about it? Because both Lukashenko and the opposition are trying to pit different groups of hired workers against each other. Tikhanovskaya and company demand independent unions for government operations while staying silent on private companies, where work conditions are even worse. Meanwhile, Lukashenko tries to set “his” government enterprise workers against the city “creative class,” the majority of which are also hired workers, only more disoriented and swindled by the liberals.

In Russia, there was a remarkable occasion, which we would hate to see repeat: when miners striking in 1993 rejected, with disdain, the solidarity of teachers, professors, and scientists, already suffering from Yeltsin’s crackdown on science and education. They were like: you’re just loafers from the capital city, try working the mines for a day. As a result, both sides were left out in the cold. Factory workers, if other hired workers join you in your fight for a better life—you will benefit from it.

Either way, a teacher, a student, an ordinary programmer, or a McDonald’s employee is closer to you than a government employee, a business owner, a general, or an ideologue receiving a hefty wage who has to play a “regular guy” once a year. If Lukashenko puts on a hard hat once in a while or reminisces on his kolkhoz past, it doesn’t make him a worker or a peasant, and it doesn’t bring his interests closer to yours and ours.

Blood isn’t water

Both Lukashenko and the opposition show everyone by ramping up the violence how cheap the blood of rank and file Belarusian is for them: whether it’s a protestor or a police officer, a worker, or a student. Meanwhile, they value their own skins very high.

That’s also how “foreign partners” size up people’s blood. Who cares that a dozen miners died? They have another tragedy at hand: poor Tikhanovskiy is in prison. We don’t know how it works for you guys in Belarus, but in Russia, wealthy opposition leaders do not share the same prison cell toilet as regular inmates—both political and criminal. But for now, the well-fed European everyman will take the crocodile tears of the poor, desolate liberals at face value.

But who over there knows about the real tragedies: about the Pinskdrevo explosion, about Moscow’s worker dormitory inhabitants thrown out into the cold, about real slaves in Siberia who murdered their slaveowner out of despair, about the massacre of protesting workers in Kazakhstan’s Zhanaozen? Who cares if a dozen or two of the aborigines died to the glory of its highness, the Capital. Like in that joke about a bear at a construction site—“those over there are Moldovans, who needs to count them?”

Therefore, from the masters’ point of view, your blood is cheaper than the blood of a well-fed European, and, most importantly, their own blood. And this shows one straightforward thing. For both Lukashenko and Tikhanovskaya, you cost as much as your labor costs. And both sides agree that the Belarusian worker should cost a little. Otherwise, the Belarusian economy will not be competitive. Lukashenko is looking at “communist” China, where workers’ rights protections are substantially lower than even in the pretty liberalized Russia. With liberals, it’s even easier—they’re card-carrying opponents to all labor or social rights.

So if someone is not convinced by any of our other arguments, and wants to take one of the sides in the “higher up” conflict, at least don’t give the masters the most worthy thing of all—your blood and your life. Blood isn’t water. And if the masters really can’t stand each other that much, let them beat each other’s well-fed mugs, instead of shielding themselves with your faces. You can stand in the distance with a little poster for a bit, if there’s some money coming in for it—the masters won’t lose much, they won’t starve.

Ed: The serf on the left asks “Why are the masters fighting?”. The right responds: “Beats me: just hope that tomorrow it’s not our scalp locks that crackle”. See below for the translator’s note on this saying.

Some conclusions

The events in Belarus aren’t just about a Maidan, or a fight amongst the masters, into which the masses of simple workers are being pulled in. The conflict has a third side—hired workers, who have their own blood interests but still lack a defined voice and self-sufficient organization. The earlier they appear and the fiercer they are—the more chances the Belarusian workers have to make it out of this mess intact. Either way, one has to make sure that no matter how much the masters fight, the serfs’ scalp locks shouldn’t crackle.Translator’s note: Russian-language proverb originating from the 16-17th century military conflicts between the Polish feudal lords big and small, in which their serfs, who had the “scalp lock” hairstyles common for the area, would do the fighting.

If you want to protect your struggle—don’t feel sorry about the Lukashenkos and the Tikhanovskayas: don’t follow the example of Ukrainian union members, who don’t want to offend the liberals.

Translated by Katya Kazbek

Text by Ivan Shogolev, a sociologist in Moscow. Bylines in Rabkor.ru, Vestnik Buri, and other left outlets. Co-founder of The Laboratory of The Future.

Images by Daur Dbar, an artist and sound engineer in Moscow.

Editing in Russian by The Laboratory of The Future collective.