What Happened When Black Students Marched on Red Square in 1963

Originally published in Moskvich Mag as «Как прошла демонстрация чернокожих на Красной площади в 1963-м»

Based on research by Julie Hessler in ‘Death of an African Student in Moscow’ in Cahiers du Monde russe, 2006.

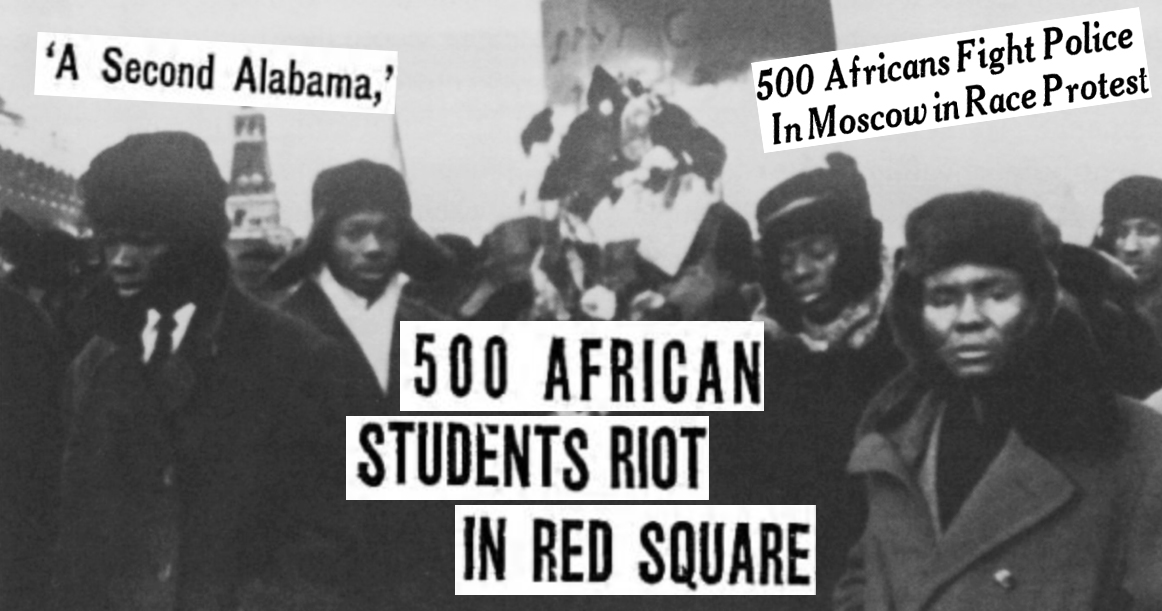

At first glance, it might seem that the ongoing protests against police brutality in America, following the murder of George Floyd in Minneapolis, have little to do with Russia. However, Moscow’s past reveals a similar story. On December 18th, 1963, the first unsanctioned demonstration since the 1920s took place on Red Square. What happened that day can serve as a reminder of our own racist history.

Seven hundred Black students marched on Red Square, chanting “Stop killing Africans!”, “Moscow is the center of discrimination!”, and “Moscow is the second Alabama!”. The demonstration was held in response to the death of Ghanaian student Edmund Assare-Addo, enrolled at the Kalinin Medical Institute, a casualty of the racism that African students faced every day in Russia.

Assare-Addo’s body was found near a backroad on the outskirts of Moscow. There were no signs of a struggle, except a small scar on his neck. How did an African student end up alone in an isolated area at the city’s edge? How did a student from Kalinin end up in Moscow in the first place? And why were 700 more African students from all around the Soviet Union in Moscow with him?

The early 1960s marked the Soviet Union’s first diplomatic forays into a newly independent Africa, and accordingly, proved a serious test for Soviet internationalism. In January 1960, the Soviet Central Committee issued a declaration endorsing expansion of ‘cultural contacts’ in sub-Saharan Africa. That February, Patrice Lumumba University of International Friendship was established. Between 1959 and 1960, only 72 African students were studying in the Soviet Union; in 1961, there were already 500. By the end of the decade, that number had more than tripled to 4,000.

For Soviet citizens, watching the popular film Circus—about a Black child finding acceptance in the USSR—and reading Samuel Marshak’s poems on racial equality were one thing. But fully internalizing their message—’racism is bad’—was another. Could authorities really be certain that Soviet citizens had gotten the message? If any such certainty existed, it did not last for long.

In March of 1960, two months after a declaration on expanding relations with Africa, a self-organized coalition of African students sent a letter to Khruschev: “Russian students have repeatedly insulted and continue to insult African students. One student was called a monkey, and two other students received an offensive letter from the Russians…the University administration and the police have not taken the necessary measures to solve this, but, on the contrary, demonstrate prejudice and bias.”

The letter was, in part, about an incident at Moscow State University. Four Russian students at a party insulted a student from Somalia for trying to dance with a Russian girl. The ensuing investigation by the Communist Party, the KGB, and the Ministry of Education concluded that the Somali student was at fault. According to the official story, the student, Abdul Hamid Muhammed, asked the girl to dance with him, but she declined and went off to dance with her friend. After the dance, Abdul Hamid spit in her face, and she slapped him in response. Other students intervened, and one demanded an apology. A fight broke out. One spectator described the rationale for fighting: “He couldn’t calmly look on while a foreigner insulted a Soviet girl.”

The embassies, universities, and organizations that brought students to the country continued to be flooded with complaints about racist harassment. Love affairs between young African men and Soviet women presented a particular point of tension. Part of the problem was the large gender imbalance among African students. As a case in point, Assare-Addo, the student found dead, had been planning to marry his Russian girlfriend.

Africans also complained about constant document checks and searches by police officers. In one case, a student from Sierra Leone went to visit his Russian girlfriend. Her neighbors called the police, who then subjected the lovers to a lengthy and humiliating interrogation. When conflicts arose involving African students, police often ignored their racial motivations. In another case, police failed to intervene when a student from Mali was being beaten, allegedly mistaking the violence for playful roughhousing. They did not offer the student any assistance afterwards, and refused to conduct an investigation.

In 1962, the Ghanaian embassy received so many complaints about racist aggression by Soviet citizens that they were finally forced to open an investigation, certified by the Ministry of Higher Education and the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. It concluded, however, that the majority of accusations were unfounded, and most cases remained unresolved. Some of them concerned provocations and insults, including one episode in the Moscow metro, when a couple of drunk Russians demanded African students give up their seats, saying, “You can’t even ride in the same subway with white people where you come from, and here you’re sitting while white people stand.” In many other cases, there was documented physical violence.

Given the authorities’ reluctance to investigate these cases, stories about them circulated by word of mouth, often distorted or exaggerated by the ‘telephone effect.’ Tensions continued to rise. If any incidents managed to get a response from officials, then their racist character was framed as an exception, “a few bad apples.”

Of course, African students were also affected by foreign policy between the USSR and their home countries. The Soviet Union used two channels in its contacts with ‘developing countries.’ Public organizations such as the Afro-Asian Friendship Society, the Komsomol Central Committee, the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions, and the Committee of Soviet Women were responsible for working with students from abroad. These organizations, which had some autonomy—albeit, a formality—selected students according to strict ideological criteria, and based on recommendations from interested parties.

Soviet political authorities, meanwhile, were less interested in supporting African countries’ radical leftist movements than in widening their Communist geopolitical bloc to oppose the West. However, appearing to act on two fronts did help get out of some sticky situations.

In 1964, radical Morrocan students, outraged at the political repressions in their homeland, occupied one of Morrocan embassy’s buildings in Moscow. Moroccan government officials contacted the Kremlin with demands to storm the embassy and deport the students. The Kremlin, however reluctantly, managed to pacify the students. As to Morocco’s other demands, it announced that they fell within the jurisdiction of civic organizations, rather than the national government. The Morrocan protesters thus remained in the Soviet Union.

The Soviet Union’s image as a society where socialism and internationalism prevailed did not often reflect its reality. Expectations clashed with lived experience, giving rise to doubts and murmurings among the students. Because of this, Soviet administrators were determined to weed out obvious rebels like Maoists, in order to ensure that revolutionary fervor was directed outwardly—at capitalism—rather than inwardly, at the shortcomings of Soviet society.

To this end, they created student organizations (primarily zemlyachestva, local groups based around members’ place of origin). The idea was that by socializing together, politically conscious students could influence their politically suspect peers: maximalists and far-left romantics, and even those hooked on the dances and parties thrown by Western embassies.

The government’s strategy backfired. Many students began to consider these societies and associations a real mechanism to stand up for their rights, an opportunity to voice their demands to the university administration. The story of the Black African Students’ Union—the first independent student organization—did not end happily.

It was founded by Theophilius Okonko, son of a middle-class Nigerian minister. Okonko renounced Christianity and, in his own words, “gained a fiery faith” in Communism after studying classical Marxist texts. Against his father’s will, he successfully applied for a UN scholarship. In 1958, he entered university in Moscow. Before long, Okonko had become secretary and spokesperson for the Black African Students’ Union.

The Union’s grievances did not address racism specifically, so much as the USSR’s politically repressive climate in general, as well as the exploitation of African students for political ends. Union activists expressed outrage when Egyptian students were expelled from MGU (Moscow State University) dorms. They’d refused to denounce Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser, who had recently come into conflict with Krushchev, and many saw their eviction as a punitive measure. Another incident involved Okonko himself. A photo of him at the gym was published without permission in The New Times, the Soviet Union’s exported magazine. In it, his wrists are shackled, trailing broken chains. He was meant to symbolize Africa, casting off the yoke of colonialism. Okonko was furious at such blatant exploitation of his image.

Authorities denounced student activists “for separatism” and for attempting to speak out about racism in the Soviet Union. As it happened, however, the organization was ultimately banned for other reasons. In 1960, students decided to organize a protest against French nuclear tests in the Sahara: a state-sanctioned subject for protest, one would assume. However, Khrushchev’s planned visit to France coincided with the demonstration. The University was ordered to prevent any unauthorized actions from going forward. First the Union’s meetings and protests were banned, followed by the organization itself, and its student activists threatened with deportation. Eventually Okonko wound up in the West, where he gave many interviews about the Soviet situation.

Soviet authorities were indignant, not entirely without cause—for example, Okonko recounted the USSR’s faults to the press in South Africa, a country which, at the time, still upheld legal apartheid. As for racism in the USSR, the party line remained unwavering: it did not exist. Okonko was accused of slander. The newspaper Trud (Labor) branded him an alcoholic, a failing student, and a spy, for good measure.

While the students’ organization had been dealt with, the problems it called attention to persisted. On December 9th, 1963, the Ministry of Higher Education received word that Ghanaian students from Leningrad, Kalinin, and Kharkov were coming to Moscow, nominally for an embassy event over the weekend. The embassy, however, had not issued any invitations. The students’ universities were ordered not to let them leave for Moscow.

Nevertheless, on December 13th, some 300 students from Ghana and other African countries congregated outside the Ghanaian embassy in the capital. Later, Ghanaian ambassador John Banks Elliott reported that students camped out in the street for four days, drinking, raising a ruckus, and interfering with work, forcing him and his family to barricade themselves in the embassy. According to Elliott, the gathering was a provocation by one of the Western embassies. He claimed the students demanded higher stipends, better housing, an expanded menu that included Ghanaian dishes (among them rice-based meals), and permission to travel to the West. Elliott called these demands impossible, from the realm of fantasy, and emphasized the students’ delinquent behavior outside the embassy. In doing so, the ambassador adopted the official Soviet version of events, which overshadowed the political nature of the demonstration.

By other accounts, Ghanaian president Kwame Nkrumah had orchestrated the unusual enterprise, summoning the students to a meeting before changing his mind at the last minute. Nkrumah was preoccupied with the idea of pan-African unity—but under Ghanaian, rather than Soviet, hegemony, and was using Ambassador Elliott to advance this agenda. Perhaps, as the story went, the students’ controversial gathering was merely one move in a long game to change the balance of power.

In yet another version of the story, Ghanaian students took initiative and organized the meet-up themselves. President Nkrumah’s regime in Ghana—the first African country to gain independence from outside rule—was looking increasingly like a one-party dictatorship. Ghanaian youth in the USSR, potential future elites, felt the pressure of their country’s political situation. It’s quite possible, as this version goes, that students intended to use the newly-formed university society as a platform to express themselves freely: on racism in the USSR, and on the situation at home.

But even if the initial impetus came from without, when Ghanaian students gathered outside the embassy that day, they were most likely acting in their own interests. Their discussions had focused mainly on publicity tactics and problems with racism. News of Assare-Addo’s death reached them in the midst of these discussions, and the students decided to boycott classes until police opened a formal investigation.

On the morning of December 18th, they came together again outside the embassy and prepared a memorandum to the Soviet authorities. After this, a group of demonstrators set off toward the Kremlin, brandishing hand-drawn anti-racist posters. Slogans included “House of Friendship - House of Discrimination” (referencing the international students’ house) and “Enough murders!” Making their way across Red Square, demonstrators stopped at Spasskaya Tower and gave interviews to Western correspondents.

Various officials from the Party and internal ministries tried approaching the demonstrators. The students refused to disperse, and demanded a meeting with the Supreme Soviet in order to submit their memorandum. They were given the option to select ten delegates. Negotiations lasted for two hours. Protestors then continued on to the Ministry of Higher Education and ensconced themselves in the courtyard at the Architectural Institute next door. Officials, including Education Minister Eliutin, were not pleased. The delegates refused to speak with them behind closed doors, proposing instead to meet the protestors outside and hear the memorandum on the street.

A meeting eventually took place in the Architectural Institute’s assembly hall, and went on for two hours. The atmosphere was, in Eliutin’s words, extremely tense. Met with vocal agreement from the auditorium, students rejected Eliutin’s claim that racist conduct in the USSR was exceptional, and read out their memorandum demanding an investigation into Assare-Addo’s death, as well as into other incidents: “We are not convinced of our safety in this country. When somebody beats us up, nobody reacts. Perhaps the minister is simply not up to date with what’s happening.”

An investigation published shortly thereafter stated Assare-Addo’s cause of death as hypothermia, alleging he’d lost consciousness from alcoholic intoxication and fallen in the snow. The questions of how he’d ended up on the outskirts of Moscow, and how the scar on his neck had gotten there, were never answered—or if they were, the answers were never made publicly available.

As a result of the December demonstration, the university intensified its ideological ‘preparation’ for African students. More importantly, greater attention shifted toward instilling the values of internationalism in the USSR.

As often happens, the effects of Soviet propaganda cut both ways. On the one hand, it did counter many archaic prejudices—including racist ones—or, at a minimum, make it “politically incorrect” to express such prejudices in public. On the other hand, it also covered up those evils where they did exist, making it more difficult to fight them successfully. This double-edged sword disillusioned many, including staunch Communists and supporters of the USSR.

Today’s Russia has inherited and amplified the worst parts of that reality. These days it’s hard to tell whether we’re patriots poised to save the “white West” from immigrants and Black people, or back in the ring with Uncle Sam, fighting for the happiness of all nations on Earth. One thing is clear: more often than not, the rejection of Soviet internationalism, for all its flaws, transforms racism from a shameful, common prejudice into something seemingly natural, almost biologically determined. In this sense, the story of how African students first absorbed internationalist ideals in theory—ideals born in Moscow, in Russia—and then showed Soviet citizens, in practice, how to fight for their rights, is very relevant at the present moment.

Co-translated by R. Neubivko and Anton Relin.

KIRILL MEDVEDEV is an award-winningAndrei Bely Prize for poetry (2014), Ilia Kormiltsev Prize (2008)

Marxist translatorVictor Serge’s Resistance, Adrian Mitchell’s Jungle Loves You, Terry Eagleton’s Marxism and Literary Criticism, Michael Löwy’s Fatherland or Mother Earth?, Charles Bukowski’s Women, etc.

, poet, musician, and political activist. It would be onerous to list the places he’s been translated, profiled, and reviewed, so with our house bias, we’d point towards his NLR article, chto delat, and Ugly Ducking Presse. His own Free Marxist Press has released translations of Deutscher, Eagleton, Pasolini, Mandel, and more, winning the Igor Zabel Association for Culture and Theory grant in 2014 for its activities.